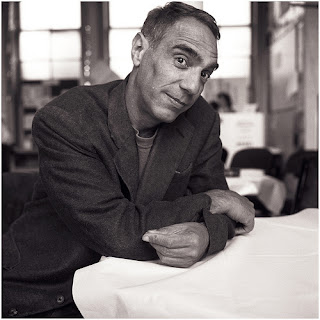

Дерек Джармен родился в Голландии, изучал изящные искусства и преуспел не только в постановке фильмов, но также как поэт, писатель и художник. Будучи вечным диссидентом, Джармен никогда не стремился к коммерческому кино. Он не заботился о сборах, гигантских бюджетах, "звездных" актерах и съемках в известных студиях, он остался в Англии, чтобы делать те фильмы, которые были интересны ему. Его работы ослепляют зрелищностью, во многом автобиографичны и не всегда придерживаются традиционного стиля повествования. Одни фильмы словно обнажают в авангардно-мифической манере его душу; другие - красочные интерпретации ранее опубликованных работ; все вместе они являются частью его неповторимой целостности как художника.

Можно просто сидеть и жалеть себя или выйти и попытаться сделать что-нибудь.

Я выбрал второе

Лицом к лицу:

беседа Дерека Джармена и Джереми Айзекса

Это интервью - часть серии бесед на тему "Искусство и мастерство кино" и было показано BBC 15 марта 1993 года.(в сокращении)

Ты всегда мог открыто говорить о своей сексуальности?

Нет, определенно нет. На самом деле, я всегда старался это скрывать. Конечно, в пятидесятых-шестидесятых годах, когда я был ещё совсем молодым, говорить о своей сексуальности было практически невозможно, и я думаю, что мне это даже давало некоторое преимущество перед остальными. Тогда вообще было довольно сложно жить, даже просто невозможно, до тех пор, пока мне не исполнилось лет 25. Особенно сложно было с родителями, хотя среди друзей было попроще. В конце концов, в возрасте двадцати двух лет я впервые познакомился с подобными себе людьми, а потом просто не мог общаться ни с кем другим, то есть, я, можно сказать, стал частью голубой мафии.

Когда ты в первый раз понял, что ты гей?

О, очень давно. Наверное, лет в девять, в семь или восемь. Я сам об этом спрашивал тысячи людей, и они тоже затруднялись назвать точный возраст. Говорили, семь, восемь, девять лет, но точно знали, что понимание пришло ещё в детстве. Поэтому мне кажется, что это так и есть. Очень сложно осознать свою сексуальность, потому что идея извращенности и распущенности постоянно пропагандируется. Об этом человек узнает даже раньше, чем начинает понимать, что такое сексуальность.

А в то время заявлять о своей сексуальности было сложнее, чем теперь, намного сложнее?

Сложнее всего было в пятидесятые годы. Особенно, если ты воспитывался, как я, в городках Королевских Военно-воздушных Сил, где все было очень строго, в стиле среднего класса. С началом шестидесятых стало проще, а особенно, когда я приехал в Лондон. Например, за все годы обучения в университете я никому не разу даже ни заикнулся о своей сексуальности, и только на последнем курсе набрался смелости рассказать об этом одному приятелю, он учился на факультете теологии и одновременно работал в церкви на Бетнал Грин роуд <в Лондоне>, в общем я пришел к нему туда и обо всем рассказал. Он, к моему удивлению, совершенно не был потрясен этим признанием, почесал в затылке и сказал: "По-моему, я уже знаю таких людей". А мне казалось, что должен был рухнуть весь мир.

Ты пропагандируешь полную открытость проблемы СПИДа. Ты полагаешь, что наше общество уже готово к этому?

Нет, совершенно не готово. Пока совсем мало таких счастливых людей как я, которые могут сказать правду. Например, я как-то разговаривал со своим врачом, и он мне сказал: "Слава Богу, что ты есть, ты - единственный мой пациент, с которым я могу поговорить совершенно откровенно". Его слова еще раз доказывают, насколько неправильное в нашем обществе представление об этом заболевании и о лечении ВИЧ-инфицированных.

Ты родился в 1942 году. А где именно?

Ну, я родился в Нортвуде, пригороде Лондона, в местной больнице. В то время там жила моя бабушка, а моя мать приехала к ней, поскольку мой отец был военным летчиком. После рождения меня практически сразу перевезли в Уиттон, на базу Королевских ВВС, это было через месяц или чуть позже после моего рождения.

Что за человек была твоя мать?

Когда она была уже пожилым человеком, любое необычное событие приносило ей радость. Так что, если кто-нибудь стучал в дверь и начинал ей впаривать какое-нибудь мыло или убеждать принять какую-нибудь новомодную религию, она такого человека всегда приглашала в дом, мне в ней это очень нравилось. Я только потом уже понял, как скучно быть домохозяйкой в Нортвуде, когда мы туда вернулись некоторое время спустя. Моя мать радовалась всему, что могло нарушить монотонность ее жизни. Она просто обожала всё, что происходило со мной, и внимательно следила за моей судьбой. Например, в то время, когда была премьера "Юбилея", мать передвигалась только на кресле-каталке, она к тому моменту уже восемнадцать лет страдала от раковой опухоли. В картине уйма людей, которые падают в обмороки, постоянно кричат и просто раздражают своим присутствием. Но, когда я ее вез по проходу между зрительными рядами кинотеатра, она сказала, что это отличное кино, а я подумал, что она все прекрасно понимает. Ей нравилась такая жизнь, она любила весь этот театральный блеск.

Расскажи мне о своем отце.

Мой отец... Время от времени мне хочется снова пожать ему руку. Он был сложным человеком. Мне кажется, никто из нас не знал, насколько он был опустошен тем, что во время войны в качестве военного пилота ему приходилось бомбить мирные города. К тому же тогда этого никто не мог понять. Теперь, спустя много лет, конечно же, уже известно, насколько это тяжелое испытание для психики человека. С отцом было трудно общаться, когда мне было четыре-пять лет. То есть, отец не понимал, что я еще ребенок, и хотел, чтобы я вел себя как взрослый. Потом, по мере того, как мы оба становились старше, он стал гораздо дружелюбнее по отношению ко мне. Мне кажется, что перед самой его смертью мы стали настоящими друзьями.

Ты хотел заниматься искусством?

Да, хотел быть художником. Но я никогда не хотел быть режиссером, это получилось случайно, но быть художником я всегда хотел.

беседа Дерека Джармена и Джереми Айзекса

Это интервью - часть серии бесед на тему "Искусство и мастерство кино" и было показано BBC 15 марта 1993 года.(в сокращении)

Ты всегда мог открыто говорить о своей сексуальности?

Нет, определенно нет. На самом деле, я всегда старался это скрывать. Конечно, в пятидесятых-шестидесятых годах, когда я был ещё совсем молодым, говорить о своей сексуальности было практически невозможно, и я думаю, что мне это даже давало некоторое преимущество перед остальными. Тогда вообще было довольно сложно жить, даже просто невозможно, до тех пор, пока мне не исполнилось лет 25. Особенно сложно было с родителями, хотя среди друзей было попроще. В конце концов, в возрасте двадцати двух лет я впервые познакомился с подобными себе людьми, а потом просто не мог общаться ни с кем другим, то есть, я, можно сказать, стал частью голубой мафии.

Когда ты в первый раз понял, что ты гей?

О, очень давно. Наверное, лет в девять, в семь или восемь. Я сам об этом спрашивал тысячи людей, и они тоже затруднялись назвать точный возраст. Говорили, семь, восемь, девять лет, но точно знали, что понимание пришло ещё в детстве. Поэтому мне кажется, что это так и есть. Очень сложно осознать свою сексуальность, потому что идея извращенности и распущенности постоянно пропагандируется. Об этом человек узнает даже раньше, чем начинает понимать, что такое сексуальность.

А в то время заявлять о своей сексуальности было сложнее, чем теперь, намного сложнее?

Сложнее всего было в пятидесятые годы. Особенно, если ты воспитывался, как я, в городках Королевских Военно-воздушных Сил, где все было очень строго, в стиле среднего класса. С началом шестидесятых стало проще, а особенно, когда я приехал в Лондон. Например, за все годы обучения в университете я никому не разу даже ни заикнулся о своей сексуальности, и только на последнем курсе набрался смелости рассказать об этом одному приятелю, он учился на факультете теологии и одновременно работал в церкви на Бетнал Грин роуд <в Лондоне>, в общем я пришел к нему туда и обо всем рассказал. Он, к моему удивлению, совершенно не был потрясен этим признанием, почесал в затылке и сказал: "По-моему, я уже знаю таких людей". А мне казалось, что должен был рухнуть весь мир.

Ты пропагандируешь полную открытость проблемы СПИДа. Ты полагаешь, что наше общество уже готово к этому?

Нет, совершенно не готово. Пока совсем мало таких счастливых людей как я, которые могут сказать правду. Например, я как-то разговаривал со своим врачом, и он мне сказал: "Слава Богу, что ты есть, ты - единственный мой пациент, с которым я могу поговорить совершенно откровенно". Его слова еще раз доказывают, насколько неправильное в нашем обществе представление об этом заболевании и о лечении ВИЧ-инфицированных.

Ты родился в 1942 году. А где именно?

Ну, я родился в Нортвуде, пригороде Лондона, в местной больнице. В то время там жила моя бабушка, а моя мать приехала к ней, поскольку мой отец был военным летчиком. После рождения меня практически сразу перевезли в Уиттон, на базу Королевских ВВС, это было через месяц или чуть позже после моего рождения.

Что за человек была твоя мать?

Когда она была уже пожилым человеком, любое необычное событие приносило ей радость. Так что, если кто-нибудь стучал в дверь и начинал ей впаривать какое-нибудь мыло или убеждать принять какую-нибудь новомодную религию, она такого человека всегда приглашала в дом, мне в ней это очень нравилось. Я только потом уже понял, как скучно быть домохозяйкой в Нортвуде, когда мы туда вернулись некоторое время спустя. Моя мать радовалась всему, что могло нарушить монотонность ее жизни. Она просто обожала всё, что происходило со мной, и внимательно следила за моей судьбой. Например, в то время, когда была премьера "Юбилея", мать передвигалась только на кресле-каталке, она к тому моменту уже восемнадцать лет страдала от раковой опухоли. В картине уйма людей, которые падают в обмороки, постоянно кричат и просто раздражают своим присутствием. Но, когда я ее вез по проходу между зрительными рядами кинотеатра, она сказала, что это отличное кино, а я подумал, что она все прекрасно понимает. Ей нравилась такая жизнь, она любила весь этот театральный блеск.

Расскажи мне о своем отце.

Мой отец... Время от времени мне хочется снова пожать ему руку. Он был сложным человеком. Мне кажется, никто из нас не знал, насколько он был опустошен тем, что во время войны в качестве военного пилота ему приходилось бомбить мирные города. К тому же тогда этого никто не мог понять. Теперь, спустя много лет, конечно же, уже известно, насколько это тяжелое испытание для психики человека. С отцом было трудно общаться, когда мне было четыре-пять лет. То есть, отец не понимал, что я еще ребенок, и хотел, чтобы я вел себя как взрослый. Потом, по мере того, как мы оба становились старше, он стал гораздо дружелюбнее по отношению ко мне. Мне кажется, что перед самой его смертью мы стали настоящими друзьями.

Ты хотел заниматься искусством?

Да, хотел быть художником. Но я никогда не хотел быть режиссером, это получилось случайно, но быть художником я всегда хотел.

А чем ты занимался в качестве художника? В каком стиле работал?

Я перепробовал все виды "измов", все, которые только можно представить, но в итоге я остановился на изображении традиционных английских пейзажей. Я пришел к этому в Северном Сомерсете, где жили мои тетки, которые всю жизнь занимались рисованием окрестных полей. И именно эти старомодные пейзажи стали моими первыми по-настоящему собственными работами. Потом, я, как известно, поступил в Слэйд , и там был модернизм, это была типичная Америка, но мы все неминуемо через это проходили.

Face to Face: Derek Jarman

In conversation with Jeremy Isaacs.

This interview, which is part of the Art and Craft of Movie making Season was originally broadcast by the BBC on 15 March 1993.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Derek Jarman, painter, writer, film maker; and in my view one of the most distinguished of our time, gardener. When you discovered at the end of nineteen eighty six that you were HIV positive you decided to let that be known; why?

DEREK JARMAN:

Jerry I did it for myself, really for my own self respect because my whole life had been a struggle to actually make my life open and acceptable. I found myself potentially in a film of a ghetto really of frightened and unhappy people who felt that they couldn't actually tell the truth about themselves, so I did it for my own self respect. I didn't do it for anyone else. If it was any help for anyone else I'd be delighted.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Have you always been able to be open about your sexuality?

DEREK JARMAN:

No, definitely not. I think it's something that I actually struggled to be open with. Certainly when I was a young man in the fifties, in the sixties it was very, very difficult and I think that gave me a sort of a slight edge you know. It was difficult finding the whole centre of one's life really; illegal in fact 'till I was twenty five, so it was difficult, particularly difficult with parents, maybe not amongst friends. Eventually at twenty two I met people, and then after that it was a sort of a clique if you like, a gay Mafia.

JEREMY ISAACS:

When did you first know you were gay?

DEREK JARMAN:

Oh way back, I should think probably nine, seven or eight. I've actually asked I should think thousands of people that question myself and nearly everyone knows; seven, eight, nine, they know pre-adolescence, so I think that's an accurate way of things. It makes it very difficult to see the sexuality, the idea of being corrupted and depraved actually goes out of the window with that because it's sort of, one learns it before one even learns about sexuality really.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Was it more difficult though to be open about it then, much more difficult?

DEREK JARMAN:

It was very hard in the fifties. I think particularly if you were brought up like I was on RAF Stations which were very fairly straight laced, a middle class home. It was easier you know after the sixties started, and after I'd come up to London. I know that for instance at University I told no-one and only in the last year actually did I mug up the courage to speak to a friend of mine, who's a theological student, as he was working in a mission down in Bethnal Green, and go over and tell him this. He to my surprise wasn't surprised and he scratched his head and he said "I think I've met people like that". I mean I was expecting that the world would fall in, I have to say.

JEREMY ISAACS:

You advocate complete openness about AIDS. Do you think we're open enough about AIDS in this society?

DEREK JARMAN:

No we're not at all. I mean there are very, very few people who have been as fortunate as I have; perhaps to be able to be open. For instance I was talking to my doctor the other day and he said "Oh thank God you're there, you're the only patient I can actually openly talk about". So I mean this shows that there's something still very much awry in our perception of the illness and also in the treatment of people who have the virus.

JEREMY ISAACS:

You were born in nineteen forty two. Where were you born?

DEREK JARMAN:

Well, I was born in Northwood; in the hospital there, which is a suburb of London. Then my grandmother lived there and so my mum was staying with her because my father was a bomber pilot. Then I was almost immediately moved up and into RAF Whitton, a month or so later.

JEREMY ISAACS:

What sort of person was your mother?

DEREK JARMAN:

Anything that happened in her old age that was out of the ordinary pleased her. So if someone knocked at the door, you know, with some sort of mad idea selling soap or religion, she'd always invite them in which I really liked. I realised much later that it was very, very dull to be stuck being a housewife in Northwood, where we returned much later, and so anything that broke this monotony was a joy to her; I mean she absolutely adored everything that was going on in my life and she thoroughly entered into it. For instance when Julia, she, was in a wheelchair -she was very ill for the last eighteen years of her life with cancer- and as we left there were people fainting and people shouting and making a nuisance of themselves. She said this is a very, very accurate film Derek as I wheeled her up the aisle, and I thought well you know anything. She loved it; she loved all of that theatre glamour.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Tell me about your father.

DEREK JARMAN:

My father; I think my father, I really would like to shake hands with my father now and again. He was very difficult. I think perhaps what none of us knew that he had fought as a bomber pilot right the way through the war, and I think that he really came out damaged in a way by this; in a way that at the time no one understood. Now of course, in more recent years, they know that this can be very psychologically damaging. He was very difficult with me when I was four or five. I mean he had no understanding that one was a child still, so one had to behave as a grown up. Much later on actually became friendlier, as we grew older together, and I think before he died we'd really become really rather staunch friends.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Were other members of your family important. What about your grandmother?

DEREK JARMAN:

My grandmother, yes she was important. There was something, I'm not quite certain where my grandmother came from. That's what was always fascinating about gran; she was an orphan. I think she probably came from Poland or maybe somewhere like that, and was Jewish and actually lived a life which was very, very different to all of her friends. I mean I can't quite explain; the furniture in the house, the colours she had. She was passionate about colour, so she had peach coloured tablecloths which I don't think anyone else had. I found that fascinating as a child.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Did you enjoy school?

DEREK JARMAN:

Yes I did and I didn't. I was a very late developer; I think partly a nervous child and unable to really concentrate on being taught really. It was only towards the end of my, my schooling, probably when I was about sixteen, that I realised that I'd been quite foolish and buckled under and started to really enjoy it. I mean I think there was an element of escape always and so there was always an element of escape in being a painter, because physically where we painted was separate to the main school buildings. That always worried me; it's worried me ever since that maybe the bases of the art was an escape from something rather than a confrontation. It's always been in the back of my mind.

JEREMY ISAACS:

That it was something which you genuinely enjoyed at that time and, and got a lift from or not ...

DEREK JARMAN:

It was very, very difficult. I mean I'm not quite certain how to actually answer that question. Certain aspects of the school were wonderful; like the teaching in particular my English master and my Art master, who actually opened up the world for me completely. There are aspects of being stuck in a boarding school which were very unpleasant. I think I had a childhood which was very removed from any forms of... I mean RAF Stations had barbed wire you know and so my dad would say "are you going to the town, are you going to the village", so it was always somewhere else. The same thing reproduced itself in the school you know, could you get out. I was conditioned to actually accept it of course by that.

JEREMY ISAACS:

I'm astonished and struck reading your books by how early your love of gardening began. Is that right?

DEREK JARMAN:

I should have been a gardener, I don't know why I wasn't. I suppose that no-one in my realm, my parents, thought of gardening as an occupation really, that a schoolboy might take it up. I'd forgotten about it but I had kept all my gardening implements, my gardens.

JEREMY ISAACS:

When did you first garden? Who said garden? Did you say "I want a garden"?

DEREK JARMAN:

I think I said it first and Villa Crosier in Lago Maggiore, when I was four and I was absolutely entranced by this place, and sunlight; an English RAF Station, camellias... There was a house which was requisitioned on the lake and I think it's there; I've got some film and I'm picking geraniums.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Did you want to be an artist?

DEREK JARMAN:

Yes I wanted to be a painter. I never wanted to be a film maker; that happened by accident, but I'd always wanted to be a painter.

JEREMY ISAACS:

What sort of painter were you? What sort of stuff did you do?

DEREK JARMAN:

Well I pottered through all the isms, you know all the isms you could imagine, and I finally caught up with sort of just straightforward English landscape painting. I found myself down at North Somerset where my aunts lived just painting the fields, and in a way these rather old fashioned paintings were the first ones I recognised as my own. Then of course I went to the Slade and there was the modernism; it was you know America, we all had to grapple with that.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Did you, did you grapple happily?

DEREK JARMAN:

Not particularly no. I found myself quite nervous. I realised I wasn't a very good draughtsman although actually the Slade gave me a distinction as a draughtsman. I think they must have not been looking.

JEREMY ISAACS:

When did you first design for the theatre, or for films?

DEREK JARMAN:

I started actually out of the Slade because you had to do a subsidiary and Nicholas Georgiatis was teaching there. I thought well, with my University upbringing, you know where I had been involved in the college theatre and everything, it would be a good thing to do. So I went in there and did theatre design as a subsidiary, but with no idea that I would actually ever... I mean when I was at the Slade I thought I would end up teaching in the school somewhere. I mean that was, the length of one's ambition really.

JEREMY ISAACS:

You designed for the Royal Ballet, you designed Jazz Calendar and you designed for Ken Russell's movies. How did that happen?

DEREK JARMAN:

Well it happened because I put some theatre designs for the Prodigal Son of Prokofiev into the Bienal in Paris and Lord Lloyd's house. The ballet critics saw it and introduced me to...

JEREMY ISAACS:

Nigel Gozley.

DEREK JARMAN:

Nigel Gozley yes, and he rang me up because he'd seen the painting in Edinburgh and he said "do you do these theatre designs?" and I said "yes I do" and he said "oh I've got a project, but I can't tell you what it is" so I said I'd be very interested. "It's the ballet" he said and I found myself being ushered in about a month later to Fred's, or maybe a couple of weeks later, to Fred's room.

JEREMY ISAACS:

This is Fred Ashton.

DEREK JARMAN:

Yes Fred Ashton, and him saying "well I can't just give you Frith Palley" because he's never done anything, "but if you go away and I'll hear some music upon the tape recorder, and make me some designs; if I like them I'll take you on" and that's how that happened. He was a marvellous teacher I; he taught me a great deal Fred I mean because I'd never really been in a theatre situation in my life and he was fun.

JEREMY ISAACS:

What do you most remember about Jazz Calendar?

DEREK JARMAN:

Nureyev, who didn't like it; I'll never forget that. Freddie said to me "look, if any of the dancers are a problem I'll sort it out Derek, but Nureyev; I'm afraid he's your problem". From the moment we started he didn't like the costume and he didn't like the material, and I was very young and he bragged me and mercilessly. As the curtain call came down -and we did get a lot of curtain calls because everyone liked it- he said "I hate the colours."

JEREMY ISAACS:

Sounds as if life was fun in those days.

DEREK JARMAN:

Yes life's always been fun actually. I mean I've always enjoyed myself a great deal. I mean it was being , the sixties in London were great fun. I think we probably...

JEREMY ISAACS:

Were you all out.

DEREK JARMAN:

I don't think that word really came until the seventies but the group of young artists I was with were certainly... I mean they included people like Patrick Procter and David Hockney and we formed a, we were always knocking on each others doors. There were great parties at that time, I think partly because it was very difficult for people to go out; the bars were so grim in some ways and so there were always being parties thrown by people like Tony Richardson, who was a great party giver.

JEREMY ISAACS:

You began to work with Super Eight Film. Can you say something about that?

DEREK JARMAN:

Well what happened was that I was painting still and doing the theatre designs and I'd done Russell's Devils by that time. Someone came to the studio with literally a home movie camera, and I said "that's an interesting thing". "Would you like to borrow it?" so I said "yes I would." I made a three minute film of the studio -this is nineteen seventy, seventy one- and I started to make these films. That was a really amusing thing to do because everyone came to watch them, so I used to be able to give these parties, wonderful parties and everyone would come. No-one would pay any attention to the films whatsoever; they were all there you know, all bought cushions and lay on the floor and we showed a proper film, sixteen millimetres. Something you know off the ... and then we would end up with the Super Eights.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Proper rude feature film.

DEREK JARMAN:

Well no they were, they were rather serious ones like the Wizard of Oz and serious films.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Is that your favourite film?

DEREK JARMAN:

It's one of my favourite films I must say.

JEREMY ISAACS:

You went on to make Happen and then direct, I think and write and direct Sebastiane. Why did you want to make that film?

DEREK JARMAN:

You know I don't really know, and I have to say the film was a huge muddle because of this; because none of us quite knew what we were up to. I mean there were, except for Paul Humphreys who was the editor and my friend Peter Middleton lit it and filmed it... It was a series of exploration because even though I'd worked for Ken on these two big films they were so big that you couldn't really get involved in a sense. I mean something as big as The Devils; I just pop my head round the door in the morning and then disappeared again. I think if we'd known anything about film making seriously the films would never have been made. That's the first thing; I just realised that you had to rely very heavily on those people who knew what they were doing and I've done that ever since, because I still really couldn't lace up a steam deck for you. I'm still semi-illiterate but what I do is, I think it's probably a good thing in a way, because it means that the people who work with you get, I hope, a bit more freedom than they would with someone who knows what they're doing.

JEREMY ISAACS:

How many of your bigger films have been thoroughly scripted in advance and how many have been part improvised?

DEREK JARMAN:

Very interesting that because if I'd made certain films that I'd written, you know, as traditional scripted scripts in the early eighties and things, my film making would be completely different. It would never have gone into the more experimental area and there were a whole series -Bob Arthur's Neutron I've been looking at them again recently- and thinking if those films... In a certain way they are films because I made them, and then the whole thing would change; the observation of the sort of areas that I'd been filming in would have changed a lot. I think those were scripted and the other ones towards the end of the... I threw the scripts out of the window.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Was Sebastiane a success?

DEREK JARMAN:

Em yes.

JEREMY ISAACS:

What was the premier like?

DEREK JARMAN:

Well it was great. We had more people queue... In those days the success was really dictated by how many people you had at two O'clock on the first day and we had...

JEREMY ISAACS:

Two O'clock in the afternoon.

DEREK JARMAN:

Yes two O'clock in the afternoon; we had a full, there were people queuing. It held the house record for years at the Gate Cinema, in fact probably still does. It certainly beat all the Fassbinder films and everything else hands down, so it was a sort of success.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Was that because of the Latin or because it was homoerotic?

DEREK JARMAN:

Oh it's the homoerotic, it was the homerotic, but we didn't know this because Jamie, who was the producer, said to me "oh it'll play one night at the ICA" and then Rommer Lovali, you know that great Italian actor, came and saw it and he said "this one's really quite wonderful" and he pushed it towards Italy and all of these film festivals for us.

JEREMY ISAACS:

What did those who saw it take from it? Did it entertain them, or did it do more than that?

DEREK JARMAN:

I think it was more to do with solidarity. I'm certain that most people would preferred me to be making a musical or something you know, but I think the very fact that there was absolutely nothing really in this particular area meant that it became a sort of rallying point for people. I still have letters from people you know, still now coming, saying this changed their lives. They saw themselves sort of represented in them one way or another, even in that, even in the Latin.

JEREMY ISAACS:

So they could be open about their sexuality because you had portrayed it.

DEREK JARMAN:

I think that helped and I think it's also helped with the HIV for some people. I mean the gist of the letters I have is that. I think so; I think it did have yes, it did have that effect. Strangely enough my father, on the first night, said that it was actually rather accurate for Forces life. I think at that moment I started to really rather like him because I felt that was quite a daring thing at that time for the Air Commodore to say in public.

JEREMY ISAACS:

How did funding, how do British independent films of that sort get funded. Is it pretty difficult?

DEREK JARMAN:

Well, I was lucky because my producer was very well connected and he managed to rustle up the odd thousand pounds or five hundred pounds here all over London; mostly from sort of rich and rather elderly gay men. Then we met one benefactor in Italy who kept on sending us suitcases of lira and who said "I never want to be identified with this project." We never had any money really to do it. I can't remember how much it ended up; thirty thousand pounds I think probably. We kept on running out, but there was always someone you know... We'd have a frantic phone call -"send us some more lira please" - and it got done.

JEREMY ISAACS:

You made Sebastiane, you made Jubilee, you made The Tempest. How have you been regarded in the British film making community as a film maker?

DEREK JARMAN:

I think it changed during the eighties. I think I would have said, it's very difficult to say that... I think that now what seems like a peculiar form of cinematic suicide has turned out to be my huge advantage as a film maker. What I'm saying is that I didn't have to adopt a cause; I sort of became one and I think this is very important.

JEREMY ISAACS:

You said once that you were the most fortunate of British film makers. What did you mean by that?

DEREK JARMAN:

Well I meant just that. I mean it seemed that my whole life needed to be uncovered and those lives needed to be uncovered and given a voice. It was a great privilege; I realised that I had to stick with this, do you know what I mean. This was the one strength for a film maker who is, as I said, semi- illiterate, but I did have that audience even if I couldn't pin two pieces of a film together they were going to come, so I think that's the advantage I had.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Your mother died in nineteen seventy eight. Were you with her?

DEREK JARMAN:

Yes I was. I'd come back from Italy the night before and she was apparently sort of alive and bright, but the doctors had said that she wouldn't survive the night. We chatted about Italy actually; all she wanted to know was about the flowers in Italy and because she had had marvellous memories in her life, when you know we'd moved out there after the war, she always thought as her happiest time.

JEREMY ISAACS:

What would you say was the effect of your homosexuality on your film making? I mean is there anything in it that you would recognise as camp or hear people describe as camp?

DEREK JARMAN:

Well, what Thorence said the end of the Tempest was the campest thing ever made- you know when the mouse came out. I hope so, I quite like that. I mean I think there's a certain daring in camp, and whereas it could be used to denigrate people... Oh decadence was another one; do you know what I mean... It was a terrible decadent film, but I began to think well decadence was the first sign of intelligence really, but it had to have that.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Has there been a lot of dressing up in your own and your friends' lives even off the cinema screen?

DEREK JARMAN:

We were always dressing up. We always wanted to present a good face to the world. I think all gay men of my generation, coming through those repressions, have this extraordinary mixture of wanting to conform and be accepted, and also sort of laughing at the same time, do you know what I mean. There's a schizophrenia in it and I certainly dressed up; I mean everyone in the nineteen sixties dressed up. Those people who didn't dress up in the sixties were weird; you had to. So I did Miss World, an ex Miss World.

JEREMY ISAACS:

You won the competition.

DEREK JARMAN:

Well, I have to say that it's the one time in my life I really wanted to win the competition and I failed at the first time, so when I went in the second time; I really went in to win.

JEREMY ISAACS:

What were you dressed as?

DEREK JARMAN:

Oh my, I don't know. I bought the most appalling dress in a second hand shop in the Kings Road; the sort of thing that looks rather like one of those hitched up curtains you know, like a theatre curtain. I dyed my hair blonde.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Why did you want to make a film of Caravaggio.

DEREK JARMAN:

Nicholas Will Jackson, who was the commissioner of this film originally, he was an art dealer and came and said "this is the film I was going to ask Pasolini to do but he's, since he's... Derek could you take this on?" and it became a sort of... You know it really was Mephistopheles in an odd way. I found out an awful lot; I rewrote that script seventeen times. It was rewritten sometimes for really wonderful people like Czechidamico, you know who'd done Senso for Visconti. It was actually an adventure and sometimes it got very depressing because it went on and on and on. I think from nineteen seventy eight it began or was it seventy nine? But actually I think it was one of the most productive moments of my life because I started to write and I went back to designing with Ken Russell in, opera.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Is there proof the Caravaggio was gay.

DEREK JARMAN:

I don't think there is particularly although I think he has to be. I mean when you start to actually analyse things, it's rather likely.

JEREMY ISAACS:

When you say it has to be do you mean reading the paintings?

DEREK JARMAN:

Reading the paintings yes, I mean I think he was. I don't think it's a word you could use at that time really.

JEREMY ISAACS:

What would you point to in the paintings that suggests that; just the portrayal of other men?

DEREK JARMAN:

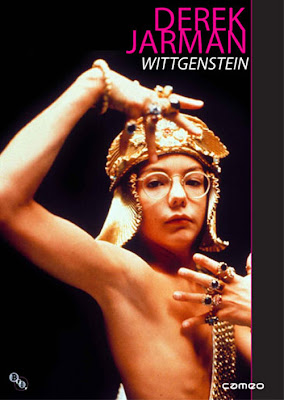

Yes and true with St. David, there's a certain... I mean I don't think it says anything particularly about his sexuality, but there is a certain sort of extremity in the way he portrays the other men in these paintings. I'm pretty certain that my reading is right, but I mean it is always a conjecture. At least I didn't actually misread in the way that was done with the Agony and the Ecstasy. I've had the same situation with Wittgenstein; it's sort of quite delicate.

JEREMY ISAACS:

That's your most recent film.

DEREK JARMAN:

Yes, yes, because again he was someone who I'm seeking in the scrolls, but-no one really says anything about it. It was interesting.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Do you portray that in the film of him or leave it out?

DEREK JARMAN:

I leave it in and I leave it as a very sad area of his life because he was very, very upset by this you know. He said it was like an icy wind blowing through his life and he says this on the film so.

JEREMY ISAACS:

You said a moment ago that em the word 'out' didn't begin really to apply until the nineteen seventies. What was the effect of that in the seventies, did people have a rare old time that they hadn't had before?

DEREK JARMAN:

No I think they probably had the same old time but it was actually more it; it was more accessible. I think what I'm saying that you know, the struggle with sexuality in say this country starts with the Bloomsbury Group. I've always wondered why people are so fascinated but it is to do with their sexuality and, and that was an uncovering... We were the generation that appropriated Bloomsbury's sexuality in the sixties in a way, and so it went on and then it became more accessible. I think you know there turned out to be many more people who were gay than one had imagined.

JEREMY ISAACS:

In your life you've had a great many I think sexual relationships or anyway a fair number of sexual relationships, some of them quite quick and casual like a lot of other gay men. Have those brought you happiness?

DEREK JARMAN:

Yes because I've always met people... I mean you know one doesn't have sex with someone and just say goodbye; one usually ends up chatting, and then you start to find out stories and lives and then you realise...

JEREMY ISAACS:

Sex first chatting afterwards.

DEREK JARMAN:

Sex, well sometimes chatting first and sometimes sex afterwards. It depends on the circumstances Jeremy really. I mean I think if you had been in one of those New York saunas and started to reveal one's life to someone, they would have been... they would have rushed away. No I think that I see it as very, very affirmative. It was a sort of, if you like, a sort of brotherhood or sisterhood this area you know. One belonged to... and there was no-one I found who wasn't, who didn't actually sort of know someone else. It was a sort of an extraordinary world of connections; so it was never anonymous in that sense. There were always these connections of places and things and these shared you know lifestyles.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Never anonymous say on Hampstead Heath.

DEREK JARMAN:

Well even on Hampstead Heath I'm known Jeremy; this is the extraordinary thing People's observation of what Hampstead Heath life is like is so, so far from reality. I mean you know everyone knows who I am, so for a start it's "good evening Jarman, what the hell are you doing here?"

JEREMY ISAACS:

Are these very quick relationships loving relationships?

DEREK JARMAN:

I think I lived with people, people who are lovers and I have had very loving relationships. They weren't always based on sexuality though you know they were really strong friendships. I've had three of those in my life and they've been, and they've been continuous. I've never talked about them simply because I was always in the position of being able to talk and the people who were involved in them didn't have a voice that I did. So actually I've always been rather discrete about that.

JEREMY ISAACS:

In your sexuality and your relationships have you learnt about other people or have you learnt about yourself?

DEREK JARMAN:

I think I've learnt both. I hope that I've learnt about other people. I think I am self obsessed. I think many artists are. I think the root cause of that might be the sexuality, but maybe not. I hope I've made people laugh a bit.

JEREMY ISAACS:

When you knew you were HIV positive, I mean the first big decision actually was the decision to be tested wasn't it, because other people didn't bother to get tested or were afraid to get tested?

DEREK JARMAN:

We were told not to; I mean that was all the received information and the wisdom at that time. A lot had happened as a friend of mine had got tested and turned out to be HIV positive and I found myself playing the role of the councillor who might be in the same situation. I decided then and there after talking to him that I would actually go and get tested myself, which I did. Making it public took a few months; I had to tell friends first. I had no idea how people would react you know. The first time for instance I walked into a room with a lot of people, after I'd actually made it public, I wondered whether everyone was going to cross you know; whether anyone was going to cross over and say hello. They all did I am pleased to say. What I discovered is that huge goodwill and human resourcefulness in these circumstances. I mean that's what I actually discovered through the illness.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Did you change your lifestyle?

DEREK JARMAN:

Yes I did, I had to. I mean I was absolutely petrified, horrified by myself. The first thing, I mean the first thing about it was that you suddenly become potentially a sort of time bomb. I just didn't know, I mean for instance I remember my friend Sarah's child -should I pick the child up-, would she... Well I would know that the child wouldn't be at risk, but she might not, so I found myself making all these decisions about contact with people. Do you know normally you'd come in through and give people a kiss and I stopped doing that because I thought some people might shy away from this, and I don't want to put them into that sort of form of discomfort. But then after...

JEREMY ISAACS:

And safe sex, did you practice safe sex?

DEREK JARMAN:

Yes I mean safe sex.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Did you chose no sex or safe sex?

DEREK JARMAN:

Well no, no sex. I mean I think I've probably had sex about two times since in the last six years which was safe sex; so if safe sex was safe then or safer- let's call it safer- then it was safer for both. The people I was involved in knew very well the, let's say, the situation and it was very important to make that public simply because it had left literally thousands and millions of people absolutely... You know no-one ever... I actually told people how to behave; there was nowhere to find out and what I needed to do was re-appropriate a sexuality which I found hugely valuable, and that's why I made that open statement in Modern Nature. I just thought it was terribly important. I got so many, again, feed back from people who said we were so frightened of ourselves; thank God you did that.

JEREMY ISAACS:

In nineteen eighty seven your father died. Where you there when that happened?

DEREK JARMAN:

No I, I wasn't and I regret this; my sister and I left.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Left the death bed.

DEREK JARMAN:

Yes. We, we couldn't face it any longer. It was very, very difficult because in his old age he became very cleptomaniac and he would steal from the family, particularly from my sister's children. We were always having... And then it got extremely difficult because my sister thought that they were stealing. They weren't; we found out through this that it was how the son said -"oh that was granddad who did that"- and then our relationships became very complicated. I have to say, you know with the children and my father coming, it got to a madness in the end; he was piling things into the boot of his car every time he came.

JEREMY ISAACS:

In nineteen ninety you became seriously ill yourself, how did you react to the implications of that?

DEREK JARMAN:

I always thought I would recover; I think we everyone does you know. Although I knew that I wouldn't in the day to day situation of being in a hospital with all these various illnesses you don't at any time... you know say I'm not going to survive this week. I would just ask the doctors "how long shall I be in here?", "oh two weeks for this one" and I'd just be two weeks... The interesting thing about a hospital is you become very dependent on it and it's a question of weaning yourself away from it; saying I can stand up, I can go and get breakfast.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Have you allowed the idea of approaching to death to dominate your life or have you managed to keep it a bit to one side?

DEREK JARMAN:

Well I think it does dominate my life and I've also tried to make space for my other self in this; it becomes increasingly difficult because you know one becomes, I've become more and more doddery really as the years have gone by. So you know it's not possible to actually ignore.

JEREMY ISAACS:

But you've gone on working and you're still working.

DEREK JARMAN:

Yes I think that that was one of the wonderful things that happened; that it was possible still to carry on working because I felt that probably I wouldn't work you know. Insurance and things like this had become too difficult. I think people have conspired to enable me to work for which I am very thankful because it shows that people who are in my situation can work you know.

JEREMY ISAACS:

You've made Edward II, you've now made Wittgenstein; what comes next?

DEREK JARMAN:

A film dedicated to Yves Klein; a blank blue film for the television, I suspect late at night.

JEREMY ISAACS:

What on earth do you mean by a blank blue film?

DEREK JARMAN:

A blank blue film. I mean a film with ... inches. I wanted to make a film about HIV and everything was so sentimental so it didn't actually... I had this great problem: I couldn't make a film about other people, I had to do it about myself. I really was, I felt that I had to make a self-portrait in the middle of all of this. I used my hospital notes and it's quite comic; I'll tell you, it's not too grim, but I thought this was a way of actually doing it with no images -you know the virus- we can't see the virus.

JEREMY ISAACS:

You live in Prospect Cottage near Dungeness and make a garden there; what pleasure does that give you?

DEREK JARMAN:

A therapy, new friends, what do gardens do? People steal cuttings; I encourage them. It's a, a whole new life. I mean there's several people come down each weekend to see the garden and they're all delightful people and they're a much broader group of people than perhaps come to see my films in the cinema you know. All the gardeners have been down there you know; Beth Chateau and Christopher Lloyd and they all rather love it.

JEREMY ISAACS:

What do you grow there?

DEREK JARMAN:

Well very little: Helichrysum, Santolina, Lavender. A Daffodil came up the day before yesterday believe it or not and that looks completely surreal in the shingles. I've got some snowdrops out at the moment and Marigolds are out still. I grow quite a lot. Actually it's quite a beautiful garden in its own way and like no other.

JEREMY ISAACS:

You're on the edge of the world down there; do you see the sunrise and the sunset?

DEREK JARMAN:

I do. The sun comes up in the front of the house and it goes down at the back and I see the sun all day if it's there. I can just, I'm fairly far back from the sea but I can see the sea; the great thing about the sea is it changes every colour you could imagine. I've seen the sea pink and brown and aqua marine and black. I sit and watch this and I was very unaware that I've been in London for thirty years and somehow you have to sit there and watch this to really realise it's happening.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Looking back on your life do you have any regrets?

DEREK JARMAN:

I don't think so Jeremy. I would prefer to have missed out on the HIV; I think everyone would've done you know, but on the other hand I take that really as a given as well and I try to turn it into a positive, a positive event in my life.

JEREMY ISAACS:

Have you anything left to achieve? You mentioned to me once that you'd like to see a statue put up to Oscar Wilde and on what will be the Centenary of the trial, is it in nineteen ninety five.

DEREK JARMAN:

Yes, it would be very nice to do that. Maybe someone out there will give us a hand; some newspaper editor or someone. I think this is the way we should do it, but yes I'd like to do that.

JEREMY ISAACS:

What would that signify?

DEREK JARMAN:

Well I think it would be wonderful to actually have a statue of Wilde which actually can focus... I mean he has that wonderful tomb by Epstein in Paris and I think it would be great to have a monument in London to him. I mean what I've seen is things have been getting better for gay men and lesbian women during my life time, and I'd like to see a situation -and there will be situations- when this is no longer a problem; it's no longer a way of cutting people off or judging people. A statue to Wilde would be -especially if it could be unveiled by a Prime Minister or a President or a member of the Royal Family or someone- would be a wonderful thing to do.

JEREMY ISAACS:

How do you want us to remember you?

DEREK JARMAN:

Well, I think it would be marvellous to evaporate. I wish I could take all my webs with me; that's what I'd like to happen, to just disappear completely.

Face to Face with Derek Jarman (1993)

Runtime: 43

Country: UK

Color: Color

Cast:

Derek Jarman

Jeremy Isaacs

This interview was part of the BBC's 1990s revival of their Face to Face series, and aired during the "Art and Craft of Movie-making" season. It was originally broadcast by the BBC on 15 March 1993.

http://rapidshare.com/files/224745724/d-j___face-to-face.part1.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/224745727/d-j___face-to-face.part2.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/224740144/d-j___face-to-face.part3.rar

Runtime: 43

Country: UK

Color: Color

Cast:

Derek Jarman

Jeremy Isaacs

This interview was part of the BBC's 1990s revival of their Face to Face series, and aired during the "Art and Craft of Movie-making" season. It was originally broadcast by the BBC on 15 March 1993.

http://rapidshare.com/files/224745724/d-j___face-to-face.part1.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/224745727/d-j___face-to-face.part2.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/224740144/d-j___face-to-face.part3.rar

Dream Machine - Derek Jarman's Films Collection (1986)

Runtime: 72 min

Country: UK

Color: Color

Director: Derek Jarman

Runtime: 72 min

Country: UK

Color: Color

Director: Derek Jarman

Witches Song (1979), Broken English (1979), Ballad of Lucy Jordan (1979) - music videos for Marianne Faithfull

T.G.: Psychic Rally in Heaven (1981) - short with Throbbing Gristle music

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0083158/

Pirate Tape (1983) - short with W. S. Burroughs

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0086110/

The Dream Machine (1983), developed by Brion Gysin and Ian Sommerville, directed by Derek Jarman, Michael Kostiff, John Maybury and Wyn Evans, produced by James Mackay

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0085459/

http://rapidshare.com/files/139046159/Dream_Machine_-_Derek_Jarman_s_Films_Collection.part1.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/139054028/Dream_Machine_-_Derek_Jarman_s_Films_Collection.part2.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/139055643/Dream_Machine_-_Derek_Jarman_s_Films_Collection.part3.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/139060686/Dream_Machine_-_Derek_Jarman_s_Films_Collection.part4.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/139063453/Dream_Machine_-_Derek_Jarman_s_Films_Collection.part5.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/139065901/Dream_Machine_-_Derek_Jarman_s_Films_Collection.part6.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/139067659/Dream_Machine_-_Derek_Jarman_s_Films_Collection.part7.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/139068976/Dream_Machine_-_Derek_Jarman_s_Films_Collection.part8.rar

T.G.: Psychic Rally in Heaven (1981) - short with Throbbing Gristle music

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0083158/

Pirate Tape (1983) - short with W. S. Burroughs

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0086110/

The Dream Machine (1983), developed by Brion Gysin and Ian Sommerville, directed by Derek Jarman, Michael Kostiff, John Maybury and Wyn Evans, produced by James Mackay

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0085459/

http://rapidshare.com/files/139046159/Dream_Machine_-_Derek_Jarman_s_Films_Collection.part1.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/139054028/Dream_Machine_-_Derek_Jarman_s_Films_Collection.part2.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/139055643/Dream_Machine_-_Derek_Jarman_s_Films_Collection.part3.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/139060686/Dream_Machine_-_Derek_Jarman_s_Films_Collection.part4.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/139063453/Dream_Machine_-_Derek_Jarman_s_Films_Collection.part5.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/139065901/Dream_Machine_-_Derek_Jarman_s_Films_Collection.part6.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/139067659/Dream_Machine_-_Derek_Jarman_s_Films_Collection.part7.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/139068976/Dream_Machine_-_Derek_Jarman_s_Films_Collection.part8.rar

Derek (2008)

Runtime: 76 min.

Language: English

Country: UK

Color: Color/black & white

IMDb Link: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1172992/

Language: English

Country: UK

Color: Color/black & white

IMDb Link: http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1172992/

Director: Isaac Julien

Cast:

Derek Jarman ... Himself (archive footage)

Tilda Swinton ... Narrator (voice)

Tilda Swinton's narration of 'Derek' knits together the almost disorientating abundance of film clips, interviews and stills. She remembers first encountering Jarman in the mid-1980s. "I had run away to join a different circus myself – Planet Jarmania. He was the first person I met who could gossip about St Thomas Aquinas and hold a steady camera at the same time, as he did at our first meeting. Derek was, for us young ones just moved to London from university or homes in the provinces, the greatest fun grown-up you can imagine being around. He wore his renegade identity like a buccaneer's cape: lightly and with gleeful pride – in fact, a proper swagger – and he made it his business to be inclusive. He spun a party out of every production meeting, every shoot day, every elevenses.

In one of the first scenes of 'Derek', Swinton reflects on how it was Jarman's wish at one point to evaporate from view and take his work with him – and how close to the truth this has become. "There is a whole generation of people who will never have heard of Derek Jarman and are just the kind of people who would love his films. And where are they? They have only recently started to be talked about being released on DVD... [They're rarely seen] on video and seldom in cinemas. You know, where are independent distributors? How is it going to be possible for independent distributors to feel powerful enough to distribute this kind of work in the future and to educate the film audience?

http://rapidshare.com/files/242828934/DEREK.part1.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/242831625/DEREK.part2.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/242834365/DEREK.part3.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/242836977/DEREK.part4.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/242839723/DEREK.part5.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/242842144/DEREK.part6.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/242844344/DEREK.part7.rar

Cast:

Derek Jarman ... Himself (archive footage)

Tilda Swinton ... Narrator (voice)

Tilda Swinton's narration of 'Derek' knits together the almost disorientating abundance of film clips, interviews and stills. She remembers first encountering Jarman in the mid-1980s. "I had run away to join a different circus myself – Planet Jarmania. He was the first person I met who could gossip about St Thomas Aquinas and hold a steady camera at the same time, as he did at our first meeting. Derek was, for us young ones just moved to London from university or homes in the provinces, the greatest fun grown-up you can imagine being around. He wore his renegade identity like a buccaneer's cape: lightly and with gleeful pride – in fact, a proper swagger – and he made it his business to be inclusive. He spun a party out of every production meeting, every shoot day, every elevenses.

In one of the first scenes of 'Derek', Swinton reflects on how it was Jarman's wish at one point to evaporate from view and take his work with him – and how close to the truth this has become. "There is a whole generation of people who will never have heard of Derek Jarman and are just the kind of people who would love his films. And where are they? They have only recently started to be talked about being released on DVD... [They're rarely seen] on video and seldom in cinemas. You know, where are independent distributors? How is it going to be possible for independent distributors to feel powerful enough to distribute this kind of work in the future and to educate the film audience?

http://rapidshare.com/files/242828934/DEREK.part1.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/242831625/DEREK.part2.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/242834365/DEREK.part3.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/242836977/DEREK.part4.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/242839723/DEREK.part5.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/242842144/DEREK.part6.rar

http://rapidshare.com/files/242844344/DEREK.part7.rar

* my art: Maldoror is dead (by Igor Vaganov)

Весьма продуктивный у Вас день выдался сегодня)))

ОтветитьУдалитьэто я так прихожу в себя своеобразно ))))

ОтветитьУдалить